by Ana Guardado

Photo by Sofia Sforza on Unsplash

From birth, women learn that their potential is squandered by the world around them. Their femininity is both a gift and a wake-up call to the injustices of the world, as they’re taught early on that nothing is entitled to them. From the Garden of Eden to Helen of Troy, it’s always men who do wrong, and women who pay the price. But it’s not until a woman gets a taste of power that she develops a burning hunger to raise all hell. It’s not until she discovers freedom that men experience true fear.

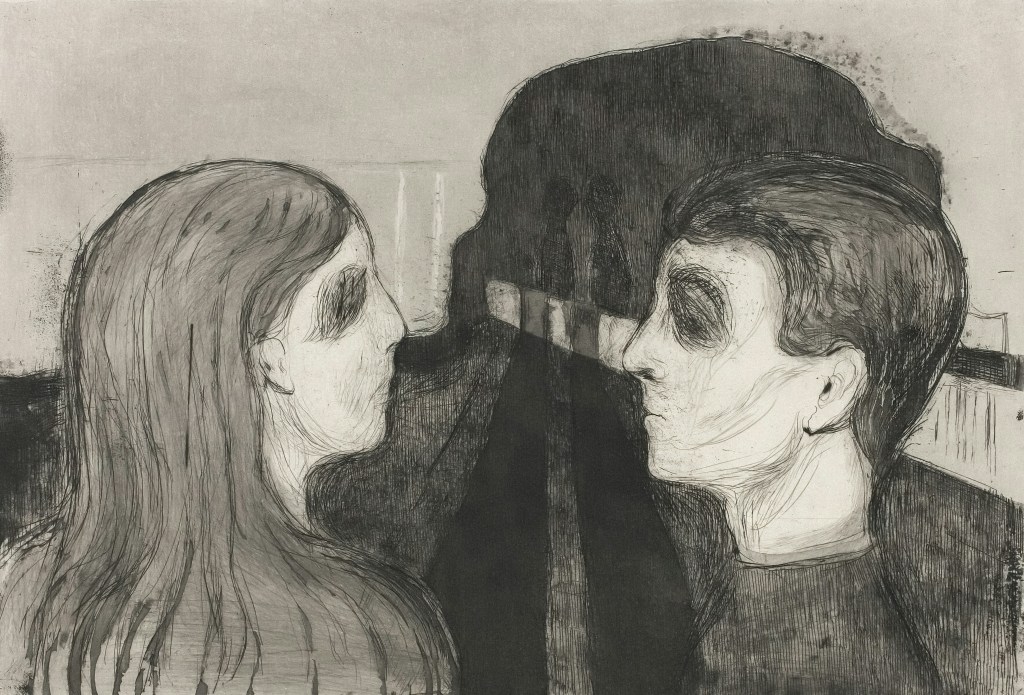

So, what exactly is a femme fatale? Translating from French as “fatal woman,” it is an archetype that gained popularity in the golden age of Film Noir in the 1940s. Sleek and sultry, the femme fatale is categorized by her seductive beauty and a single goal: to kill all men. Jennifer from Jennifer’s Body, Catwoman from The Batman, and The Bride from Kill Bill are examples of the trope in modern media. Unapologetically valuing her appearance, she’s always two steps ahead of the men who desire her, never letting anyone get too close.

This trope gained a cult following of women who admire the femme fatale’s power and confidence. In a world that calls women vain and aggressive when they dare to be beautiful and assertive– it’s exhilarating to see a character who embraces her labels with such radical force. In a way, it vocalizes women’s rage, an act of defiance after a lifetime of suppression. But is that all there is to the femme fatale? Is she defined solely by her resentment of men? To truly understand her, we must look further.

Women in the early 1940s experienced a major shift in society. With men off to war in Europe, they were left to keep the world turning round. Not only were women taking the workforce by storm, they were also populating industries formerly only occupied by men. They became welders, lab technicians, air force pilots. For the first time in their lives, they realized they were capable of anything.

Not only that, but they began to earn their own income as well. They didn’t have to answer to their husbands, and experienced true economic and societal freedom. But once men returned, it was swiftly ripped away. The country was launched into an era where no one felt normal. Men who suffered from PTSD attempted to settle back into their old lives, moving on into a new decade that wanted to forget the harrowing past. The grittiness of post-war sentiments inspired the darkness in film noir movies, and the hunger of the displaced woman inspired the femme fatale.

Film Noir’s “Femme Fatales” Hard-Boiled Women, written by Julie Grossman, explores a new facet of the femme fatale’s identity. Often portrayed as a corrupt housewife or elusive temptress, the femme fatale is meant to be seen as the opposition of the male protagonist in film noir. The man is solitary and cynical, while she is a distraction that aims to make him falter. But Grossman argues that the femme fatale is just as hardened and isolated as the male protagonist. Now reduced to her domestic box, the femme fatale simply tries to grasp onto a semblance of power she once had. She is navigating a new era that doesn’t want her anymore, that gave her a taste of what life could be, before taking it all away. Thrashing desperately so she won’t sink, she’s hardened by the rejection and suppression of the men around her.

Grossman writes, “Unlike the hard-boiled male detective, the hard-boiled female protagonist is truly alone… Mae Doyle’s expectations for domestic contentment are diminished to the point that what she finds most attractive in Jerry is that he’s a man “‘who isn’t mean and doesn’t hate women.’” The femme fatale’s violence is simply a projection of men’s anxieties and desires. They are inexplicably drawn to her alluring sexuality, but know that it gives her power over them, that she can outwit them without a moment’s notice. So, they rewrite her as aimless and sinful, only focused on the ruination of his name. What they fear most is a woman not controlled by men, so film noir presents her independence as a threat to society.

A new challenge is to imagine the femme fatale as a multidimensional, non-violent version of herself. What is she really like when not a victim of men’s projection and gender norms? What can her ambitions really make her capable of? It is interesting to think of why women are so drawn to this character, why they emulate her despite the negative portrayals. But when a narrative is skewed against a single population, it is natural for them to react with a cutthroat vengeance.

Ana is a Creative Writing major and Film minor. She is currently an editorial assistant for the Kudzu fiction team. She loves reading, graphic design, and photography.

Want to read more? Check out our most recent posts below!

Leave a comment