by Michelle Chadwell

Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash

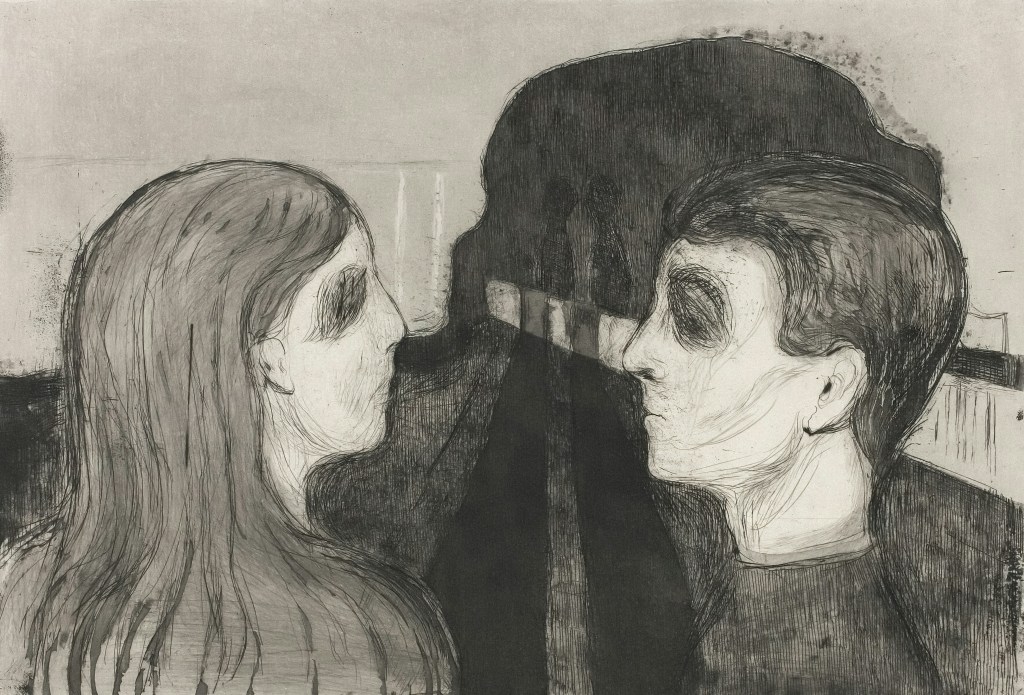

In 1967, French literary critic Roland Barthes pushed against the traditional practice of literary criticism that places the intentions and biography of an author at the forefront of discerning meaning in a text. In his essay The Death of the Author, Barthes asserts that when writing begins, the author enters his own death. Barthes claims that when a piece of art passes into the reader’s hands, it belongs entirely to them. The Author thus becomes dead and cannot assert any posthumous power upon the way we read the work.

We still see proponents of this ideology today. Though their rallying cry is less intense than Barthes’s and you may not hear calls for the “death” of the author anymore, you do hear calls to separate the artist from the art.

Barthes criticized how “the explanation of a work is always sought in the man or woman who produced it.” But how are we to kill the author in today’s ever globalizing and modernizing world wherein authors can log on to (formerly) Twitter.com and grant addendums to their works even after it has been published? How can the author truly die when their fans can open Tumblr and directly ask their favorite authors about the fate of their favorite characters?

The most infamous example of this is none other than J.K. Rowling, whose Wizarding World expands far beyond the original series. Rowling has been active on multiple corners of the internet, actively fostering and growing her Wizarding World. Poor Barthes is rolling in his grave.

After the publication of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the final novel in the series, Rowling appeared at Carnegie Hall in 2007 to answer any burning questions that fans may have. One fan asked about whether Dumbledore had ever found love, to which Rowling replied that she had “always thought of Dumbledore as gay.” This was met with equal loads of praise and backlash. Many applauded Rowling for the representation, but it begs the question: does representation for representation’s sake really matter when it isn’t in the canon text? In this case, Rowling is merely claiming representation without doing the actual work of giving justice to that representation. It is a gross tokenization of the LGBT community, perhaps for the sake of staying relevant.

Even when given the chance to codify Dumbledore’s sexuality in the canon text, Rowling still refused to explicitly do so. Still, she continues to assert only outside of the canon that Dumbledore is a gay man. Rowling’s return to the Wizarding World with 2016’s Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them was a prime opportunity to put her money where her mouth was and represent the strained queer relationship between Dumbledore and Grindelwald that she has been telling fans about for almost a decade. Yet, the release of three movies in the Fantastic Beasts franchise have come and gone, and there is still no substantial textual evidence of Dumbledore’s sexuality. Are we to accept Dumbledore as queer representation simply because the author says so?

Dumbledore’s sexuality is not the only time that Rowling has granted post-publication addendums to her works. Her Twitter page contains answers to fan questions amidst a slew of harmful transphobic tweets. On the very same platforms where Rowling discusses the intricacies of her Wizarding World, she is not shy in voicing her transphobia. She is a proclaimed TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminist), a person whose views on gender identity are extremely hostile towards transgender people.

This introduces a paradox regarding the potential killing of an author. If you take Barthes’s words to heart and throw authorial intent out of the window when consuming an artist’s work, are you trying to enhance your understanding of that work by separating yourself from the intents of the author, or saving yourself from the potential guilt of discovering that your favorite author is a raging bigot?

In an era where the relationship between the artist and the art is culturally significant, where discussions of ‘cancel culture’ remain prominent in online discourse, can we ever really kill the author? Can you trust your opinions in consuming a work of art when the author can easily get on Instagram stories and explain it all away? Barthes claims that once the piece of art has passed from the author’s hands, it belongs entirely to the reader. But it seems like authors are intent on holding their readers’ hands through their novels to make sure readers understand what the authors want them to understand. If I were to read Harry Potter again now, it would be impossible not to feel haunted by the ghost of J.K. Rowling, peering behind my shoulder and breathing down my neck.

Michelle Chadwell is a junior at FSU and head editor for Kudzu’s nonfiction section. She loves to provide her hot takes on all things literary and is double majoring in Literature, Media, and Culture and International Affairs.

Leave a reply to John Sciabbarrasi Cancel reply