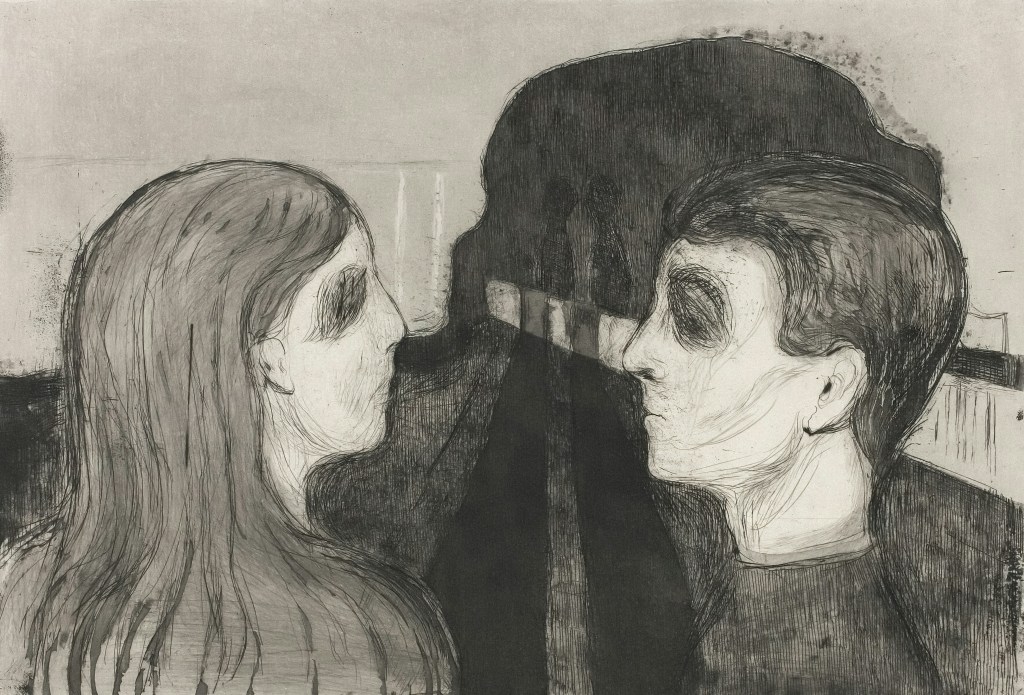

Inspired by her growing frustration with the rise of misogyny and reading of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Marlee Gaitanis wrote “First Love,”—an allegory that explores the male perspective of the objectification of women. Gaitanis is a senior dual majoring in Actuarial Science and Editing, Writing, and Media who has a deep love for gothic literature. Fascinated by the epistolary format often found in the genre, Gaitanis crafts a narrative that follows Liam Burke, a male artist whose obsession with the woman in his dreams reduces them to mere objects of his desire. For Gaitanis, writing “Frist Love” became both an outlet and a hope to bring awareness to the insanity of debasing women as objects for the pleasure of men. “It sucked to feel helpless, like there was this growing mass of people that needed me to prove my personhood to them,” she states. To confront this issue, Gaitanis blends gothic horror with modern concerns, to create “First Love” which explores not only the dangers of objectification but also the chilling truth that love and objectification cannot coexist. Her story was later published in Kudzu issue No.73 for her exceptional narrative of Liam Burke.

Told through a series of letters, Burke shares his journey for an assignment where he must encapsulate the human form perfectly into stone. He decides to recreate the beautiful naked woman who had recently appeared in his dreams because of a pendant that a friend gave him. At the start of her creation, Burke struggles capturing the essence and beauty of the woman, blaming his skill as an artist. He becomes infatuated with the perfection of her, preventing him from eating and only sleeping in hopes of the woman comforting him in his dreams. After finally perfectly encapsulating her essence in stone, he comes to the realization that she is imperfect. The minor chips in the stone and the symmetry of her breast become unbearable. Her nudity, once ethereal now appears whorish and her eyes, once radiant, now seems dull and lifeless. Burke attempts to fix the statue, but the more he tries, the more he questions why he thought she was beautiful in the first place. Ultimately, he destroys his creation, remembering her last appearance as repulsive and sloppy.

Burke’s so-called love was never about the woman herself, it was about his ability to control and shape her to his liking. The moment she became real, solid, and changeable, she ceased to be perfect in his eyes. And if he could no longer mold her, if she was no longer his ideal, then she was no longer worth existing. “He destroyed her not because she was no longer beautiful, but because she was no longer his.” Gaitanis notes. Liam’s attraction to the woman is based entirely on how she appears in his dreams. She has no voice, no agency, and no identity outside of his mind. He never considers who she might be as a person; he only considers how she looks and how she makes him feel. “It’s a very selfish kind of love, if I can even call it that,” Gaitanis adds.

As misogynistic rhetoric resurfaces in modern discourse, it is more important than ever that writers are calling attention to the insidious ways in which objectification and dehumanization continue to shape society’s perception of women. Marlee Gaitanis takes initiative by creating an allegory that forces the reader to feel the horror of the objectification of the nameless woman in Burke’s dreams. “Even if it’s not clear if the woman in his dreams is real, the very idea that she might be, of being at the mercy of such a man, is truly bone-chilling,” Gaitanis reflects.

Brianna is a senior at Florida State University majoring in Editing, Writing, and Media. Brianna loves reading, digital design, and videography. After graduating she plans on getting her masters in Rhetoric and Composition.

Leave a comment