People were made to read and write poetry. Cliché as that concept has become in the literary zeitgeist of today, it’s also true. Poetry is one of the pillars of human experience, passing from artistic expression to something we create and consume for ourselves, and for others. Confessional poetry captures the essence of the craft, distilling the personal and making it public. To exist in the world and go on to write about it takes guts. That’s the bottom line of confessional poetry– Courage.

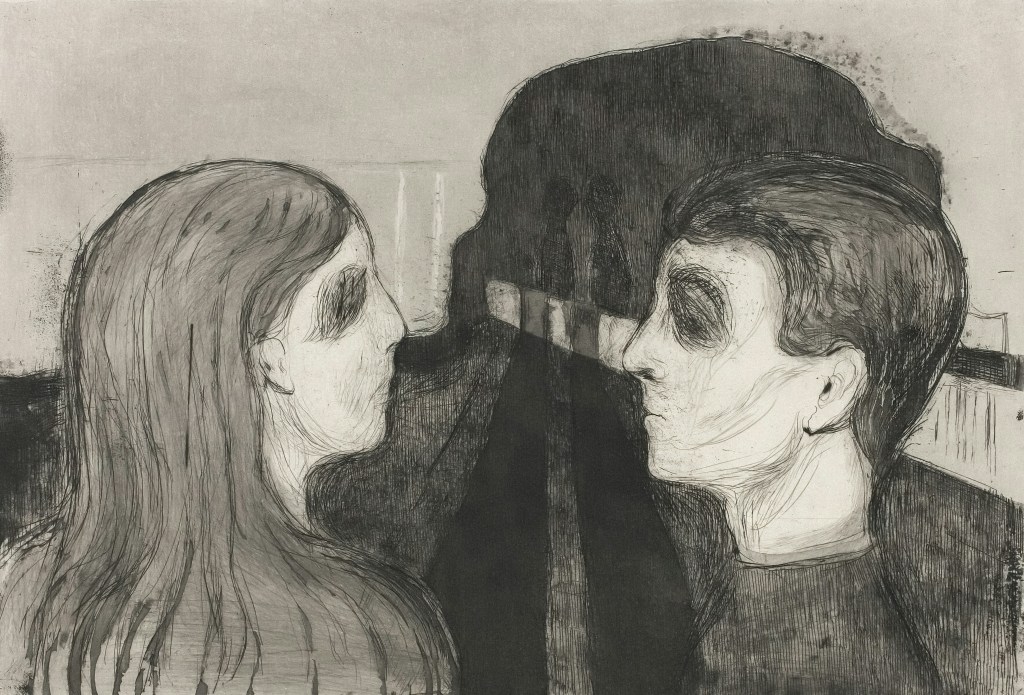

Poetry, like people, is a diverse creature. There are the epics, the lyrics, the oral traditions, the songs, the prayers, and everything in between. Confessional poetry traces its roots back to the postmodernist movement of the mid-20th century, where a new generation of writers began openly expressing their experiences and emotions about an ever-changing (and increasingly foreboding) world. There were more formal, high-brow poets like Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, who wrote openly about womanhood and trauma in an era that stifled the feminine experience. Later, the more “gritty” realists emerged, like Charles Bukowski, who brought the dark underbelly of American society into the light, flaws and all. So, it begs the question, what does it mean to “confess”? For confessional poets, the act of confessing is not only an admittance of action, but the free expression of what is deemed unacceptable or taboo in regular society, and to some degree, regular art. The situations these poets opined about were not extraordinary– On the contrary. The relatability of their experiences is an olive branch to the reader. Take my hand, these poems say, and I will show you a reflection of yourself.

There is a certain critique of confessional poets that frames their work as juvenile, low-brow, and reaching only the shallowest depths of human experience. This criticism (particularly when it comes to accessible poetry, which confessional tends to be) might have something to do with the fact that many confessional poets find an audience and voice with young people. Sylvia Plath wrote prolifically during her years in university about her own struggles with mental illness, and there are more than a few young poets who have found solace and relatability when reading those works that reflect their own lives. Young adulthood is ordinary and tumultuous, as is everyday life, and this echoes in the poetry being published by university-aged poets today. In Issue 71 of The Kudzu Review, the poem Chiaroscuro Atlas muses about the “weight” of artistry when compared to daily life, blending larger-than-life imagery with the mundane, coming together to paint an incredibly relatable portrait that nearly every creative can understand. Chiaroscuro Atlas is a tribute to postmodernism and confessional writing, creating something beautiful and accessible. This is the legacy and impact of confessional poetry– Relatability is not a fault, but a principal strength.

Poetry can be anything, but it is perhaps most effective when made accessible through personal experience and expression. Young writers and creatives are burdened with the demand to be both original and traditional, unconventional yet tame, adhering to the “rules” of the craft while maintaining personal artistic integrity. If there is one thing we can learn from confessional poetry, it is that this practice bends the rules of traditional writing by expressing humanity it it’s most honest form. If you’re looking for your next great poem, consider peeking inside yourself first. The confession is already there– You just have to be brave enough to write it down.

Veronica Fletcher is a senior at Florida State University and an editorial assistant for Kudzu Poetry. She is passionate about accessible art and writing, or more succinctly, “poetry for the people”. She likes plants, kitschy horror films, and her cats.

Leave a comment