by Daniel Fairman

Review: Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke

Photo by frank mckenna on Unsplash

The poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke began with a conviction that the emptiness of human longing ought to be transformed into something else.

“That is longing: to dwell in the flux of things,

Rilke (Poems)

to have no home in the present.

and these are wishes: gentle dialogues

of the poor hours with eternity”

For Rilke, longing was the seeking of God, not as we read him in any religious text, but as mystics who find the transcendental in babbling brooks, in solitary caves in great mountains, in the archaic statue of Apollo, in the vast night. A reflection of ourselves in the grandness and mysteriousness of the universe around us. It is no simple thing, but a deep yearning that calls us, persistent, and implores you to live the questions themselves and “go to the limits of your longing.”

Art, he argues, must be born from necessity, longing inextricable to creativity. The only way to delve into that longing is through reflection and solitude. The development of Rilke into one of the great poets demanded a descent into the terrible and painful sense of his own emptiness and longing.

“Letters to a Young Poet” is a collection of letters written between a young officer cadet from Neustadt, Franz Xaver Kappus, and Rilke.

The first letter is a response to Kappus who “unreservedly laid his heart bare as never before and never since to any second human being” begged for advice on the quality of his poems. Rilke refused, saying “You are looking outward, and that above all you should not do now. Nobody can counsel and help you, nobody. There is only one single way. Go into yourself. Search for the reason that bids you write; find out whether it is spreading out its roots in the deepest places of your heart, acknowledge to yourself whether you would have to die if it were denied you to write. This above all – ask yourself in the stillest hour of the night: must I write? Delve into yourself for a deep answer. And if this should be affirmative, if you may meet this earnest question with a strong and simple ‘I must,’ then build your life according to this necessity.”

The search inward relates not only to writing but to anything you deem worth pursuing. The magic you are seeking is in the thing you’re avoiding. What do we neglect in favor of empty consumption that does not nourish us?

The words of Rilke are especially relevant for our own time, where at our fingertips is an unfathomable collection of easily accessible distractions, the entire archive of the world’s history. How easy it is to neglect yourself by consuming endless content and avoid the difficult questions of the self. After the effort exerted from everyday living – school, work, cooking, cleaning – how can we muster the energy to spend time with ourselves, face unreservedly what is within.

Yet, it is exactly solitude, the task of seeking, which can attempt to answer the deep sense of longing, “You are so young, so before all beginning, and I want to beg you, as much as I can, dear sir, to be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart, and to try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms and like books that are written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given to you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now… love your solitude and bear with sweet-sounding lamentation the suffering it causes you.” It is a task of patience and present awareness, an act of self-love in which we pay attention to what is within.

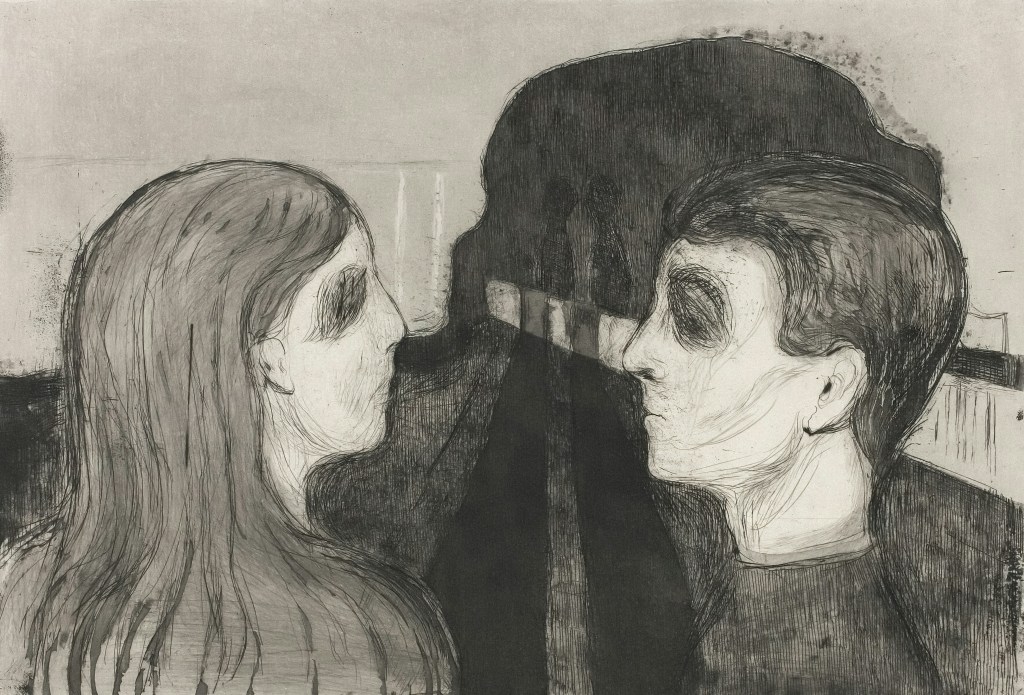

Rilke holds solitude as sacred above almost all things, especially in his creative process, so much so that his definition of love “consists in this: two solitudes that meet, greet, and protect each other.” There is no possession of another, only mutual growth, admiration of two individuals. In that solitude is a vast depth to be explored, “Think, dear sir, of the world you carry within you…whether it be remembering your own childhood or yearning toward your future – only be attentive to that which rises up in you and set it above everything that you observe about you. What goes on in your innermost being is worthy of your whole love.” (38)

Rilke’s philosophy encourages people, as Buddhists suggest, not to resist feelings of tension, sorrow, and pain, but to welcome them as they flit by like a passing cloud: “We have no reason to mistrust our world, for it is not against us. Has it terrors, they are our terrors; has it abysses, those abysses belong to us; are dangers at hand, we must try to love them…Why do you want to shut out of your life any agitation, any pain, any melancholy, since you really do not know what these states are working upon you?” (52)

In our solitude we do not escape from the world, rather make it ours. The terrors and danger are ours. We must claim them for they are us. The practice of embracing aloneness is a method in which we are able to connect with the world and yet be protected.

If we are comfortable in our solitude, we hold amid unfamiliarity a home which we can always find. “We are solitary. We may delude ourselves and act as though this were not so.” It is through Rilke one can learn to embrace our natural condition, to ask again and again the root and stem of longing which goes deeper than we can fathom, yet still go as far as we can.

Without the joy of finding ultimate truth, which is impossible unless we accept a lie because infinitesimal man cannot comprehend even the scale of the universe, let alone the scale within ourselves, we must resort to finding joy in the seeking and at Rilke’s suggestion live the questions now.

Daniel Fairman is a senior at Florida State University studying English with a focus on Creative Writing and a minor in History. He is an editorial assistant for the nonfiction section.

Want to read more? Check out our most recent posts below!

Leave a comment