by Gianna Birkeland

Spoilers: Black Swan, Where the Past Begins, and The Kitchen God’s Wife

Photo by Krzysztof Kowalik on Unsplash

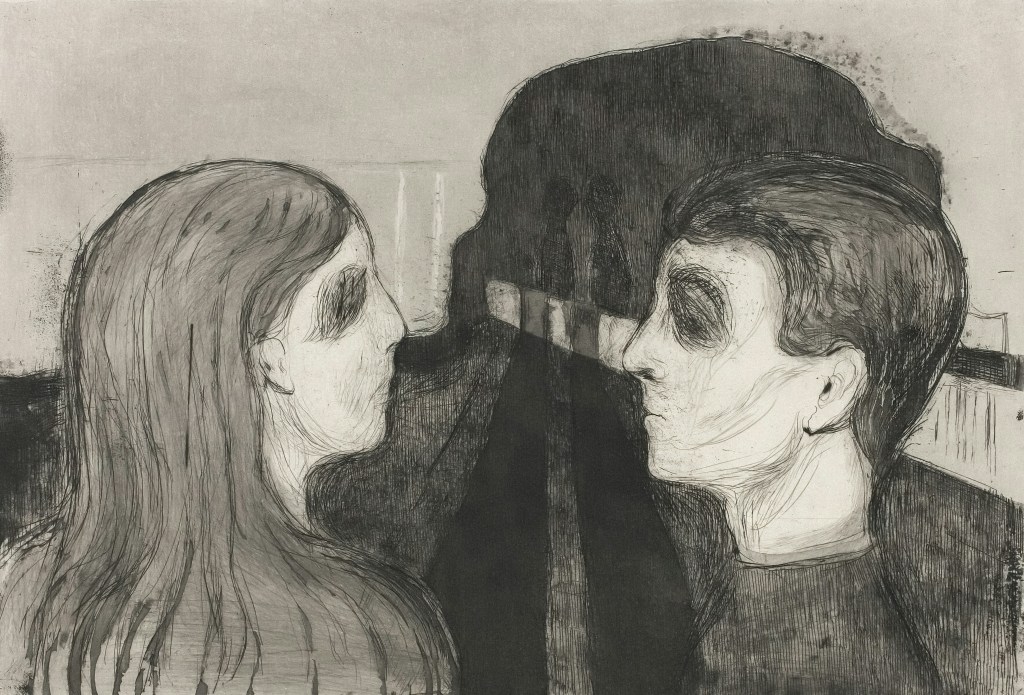

Mother-daughter relationships have become a hot topic in American media. This bond can be seen in the stereotype of a rebellious teen daughter fighting for emotional dominance from a cold, domineering, or infantilizing mother. Literature, movies, shows, and even documentaries will dissect and examine what makes this interpersonal relationship so enveloped in tumultuous cycles. While Amy Tan’s fiction aims to complicate this dynamic through her stories, many take a more one-dimensional approach.

Whether it be Gilmore Girls, where the closeness of Rory and her mother Lorelai borders on codependency, or even the more notorious ‘evil stepmother’ of Disney classics, mothers have been seen time and time again as ‘bringers of conflict’ in many dynamics.

Films such as Black Swan delve into the tendency of mothers to infantilize their children. Main character Nina, a ballerina in her mid-twenties, lives with her mother in a small New York apartment with baby pink wallpaper, a stuffed teddy bear, and a twin-sized mattress. Nina’s mother belittles her mental faculties and maturity, leading Nina to disassociate and experience hallucinations. Her mother’s infantilization is an emotional power hold, forcing Nina into a psychological corner that becomes the premise of her metamorphosis into the infamous Black Swan.

What I like about Amy Tan, however, is the type of ‘mother-daughter,’ relationships that she portrays. Raised as a second generation Chinese American, her story as an author arose from having a mother with faults. Her mother did not have a baseless sense of control, but was stricken by her history and childhood.

Tan released a memoir that I especially love, detailing a a heartfelt and genuine account of how her mother’s past intrinsically inspired what Tan writes in fiction. It is titled Where the Past Begins, and details her relationship with her mother, the intricacies of their dynamic, and how she overcame these differences later in life.

There is a quote that encapsulates this sentiment, which reads, “But when I was grown, she was inextricably part of the way I thought and observed, and to wish she were not my mother would be wishing I were a different person.” I highly recommend anyone read this, as it is a very impactful novel and challenges the mother-daughter complex in media with a nuanced, vulnerable, and transparent take on maternal relationships. As a trigger warning, it does contain mentions of suicide, death, and mental strife, due to the nature of Tan’s mother and her history. Yet it is worth the read.

The beauty of Tan’s fiction is the way in which she sympathizes with this dynamic and does not cut corners in portraying a vulnerable parental figure. In the case of Tan, her stories are carefully woven pieces of fiction inspired by her own mother. Her take on the mother-daughter dynamic demonstrates that while a mother might be domineering and controlling, she was once a daughter with a hidden history, one with beautiful and heavy scars that carry on through the next generation to come.

There is a novel by Amy Tan that I especially love, called The Kitchen God’s Wife. In it, Winnie and her daughter Pearl clash head-to-head, with Pearl being chastised for her taste in men and picking those who she knows will treat her poorly. It is only once her mother writes old Chinese print letters with failing memory that Pearl learns the vulnerable truth of her mother’s first marriage to a terrible husband. This husband had caused her to flee from China, marry, and project these fears and concerns onto Pearl in the form of an overbearing nature. Pearl and Winnie struggle to communicate, not in a surface-level feat of jealousy or want for power, but out of the most sincere, complex, and dedicated motive: love.

The best part of this motive is that it comes from a place of truth, as Amy Tan incorporates her life and emotions into her fiction writing. The story of Tan’s mother, who’s abusive first husband was the inspiration of the novel, directly translates in her writing in a way that is both genuine and complex.

These stories and novels hold a hidden history, one that has meaning, substance, and above all, a sincerity that defies the constricting label of ‘rebellious daughter versus domineering mother.’ As Tan puts it in her memoir, “The writer can put them into a story that never happened and yet did in the deepest of ways.”

Gianna Birkeland is an editorial assistant for the nonfiction section of The Kudzu Review. She is a junior with a major in Creative Writing and a minor in Spanish. In her free time, she enjoys writing poems, bird watching, and making home-cooked meals for friends. Inspired by the novels of Amy Tan, J.D. Salinger, and J.R.R. Tolkien, Gianna hopes to write seriously outside of college.

Want to read more? Check out our most recent posts below!

Leave a comment